Narcissus

Daffodil

We call someone who is obsessively concerned with their own beauty or importance a ‘narcissist’.

But what does my name have to do with them? OK, it’s like this…

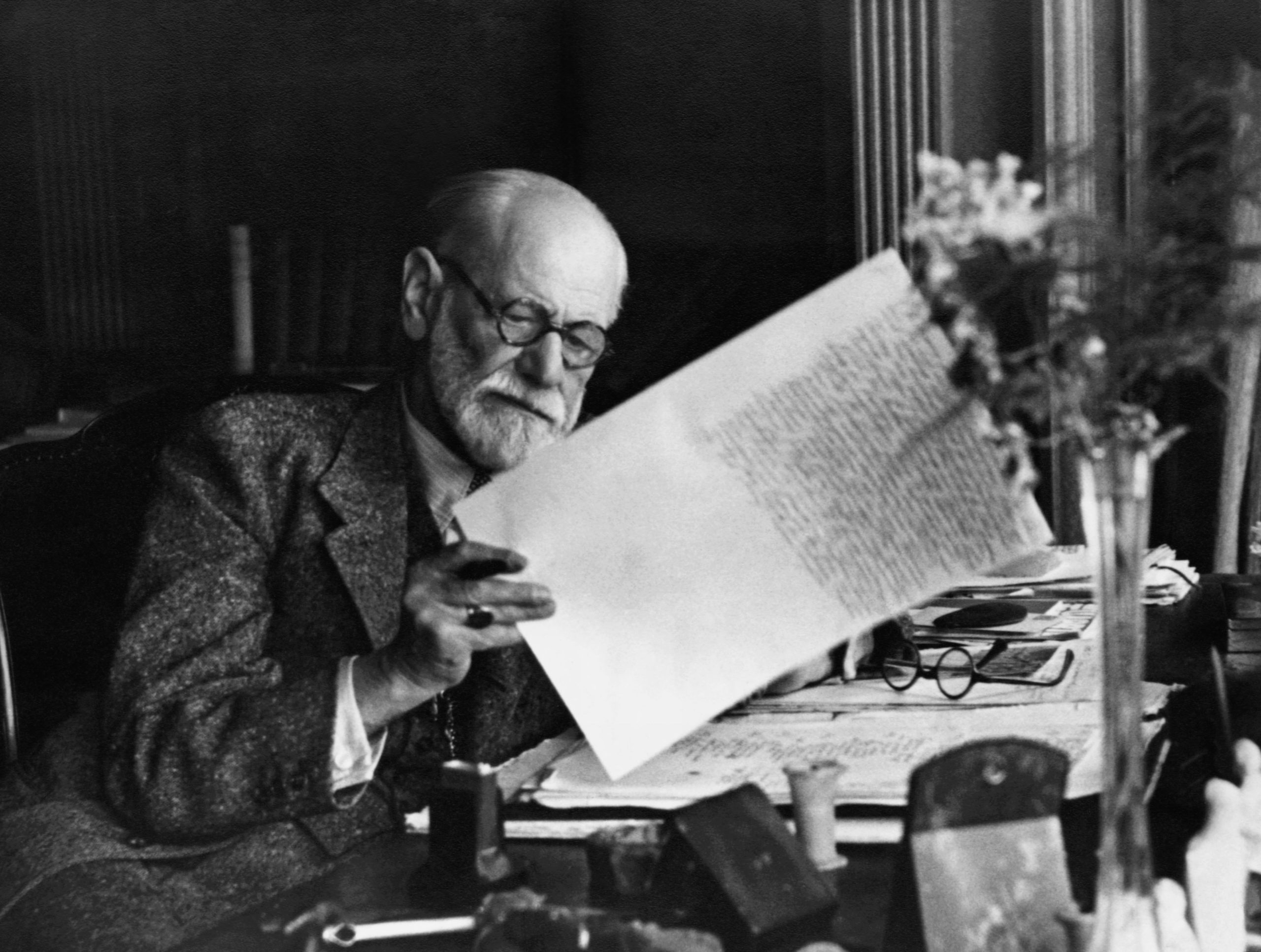

Around 1900, the famous Viennese psychiatrist Sigmund Freud was the first to use the term ‘narcissism’ to describe people who feel innately superior to everyone around them.

But he actually stole the idea for this word from someone else: Ovid.

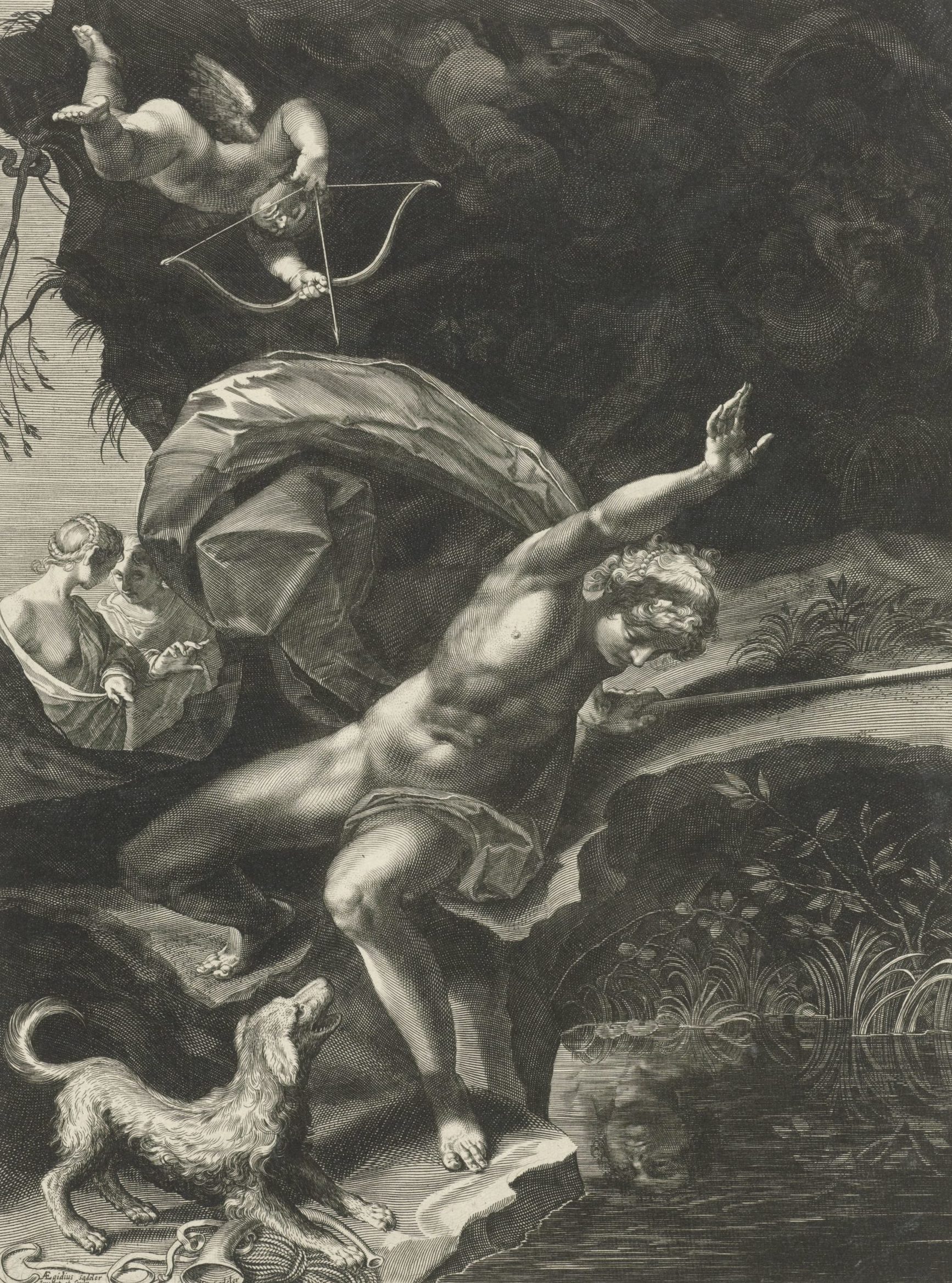

In ‘Metamorphoses’ the great Roman poet Ovid told of the tragic fate of Narcissus (Nárkissos).

This Greek boy who was so beautiful that everyone fell in love with him – including a nymph called Echo.

But vain Narcissus scorned her love, and was punished by the gods as a result: from that moment on, he would love only his own reflection.

Sure enough, Narcissus saw himself reflected in a pool of water and… wow! What a beautiful boy!

He fell in love – with himself. An impossible love, of course: no matter how he tried, he could not kiss himself.

Desperate, and heartbroken because his love would never be reciprocated, Narcissus melted away, eventually turning into me, the daffodil, a flower that is always bent towards the ground.

My Dutch name ‘narcis’ is taken from the Greek word nárkissos and is linked to the mythological figure of Narcissus.

But it can’t be ruled out that my name was also originally linked to the Greek word ‘narkè’, which means ‘numbness’ or ‘torpor’ – think of the word ‘narcosis’, derived from the Greek ‘narkosis’, meaning ‘anaesthesia’.

This also alludes to the strong smell some daffodils have, which is said to make people sleepy.

The word ‘daffodil’ comes from the medieval English word ‘asphodel’, from ‘asphodelus’, the name the Ancient Greeks used for a flower they thought was identical to me.

Which is very strange, because the flower looks nothing like me, and isn’t even family.

In France they have a more logical name for me: jonquille.

The word comes from the Spanish ‘junquillo’, a diminutive of ‘junco’, meaning ‘rush’ or ‘reed’, for my slender leaves.

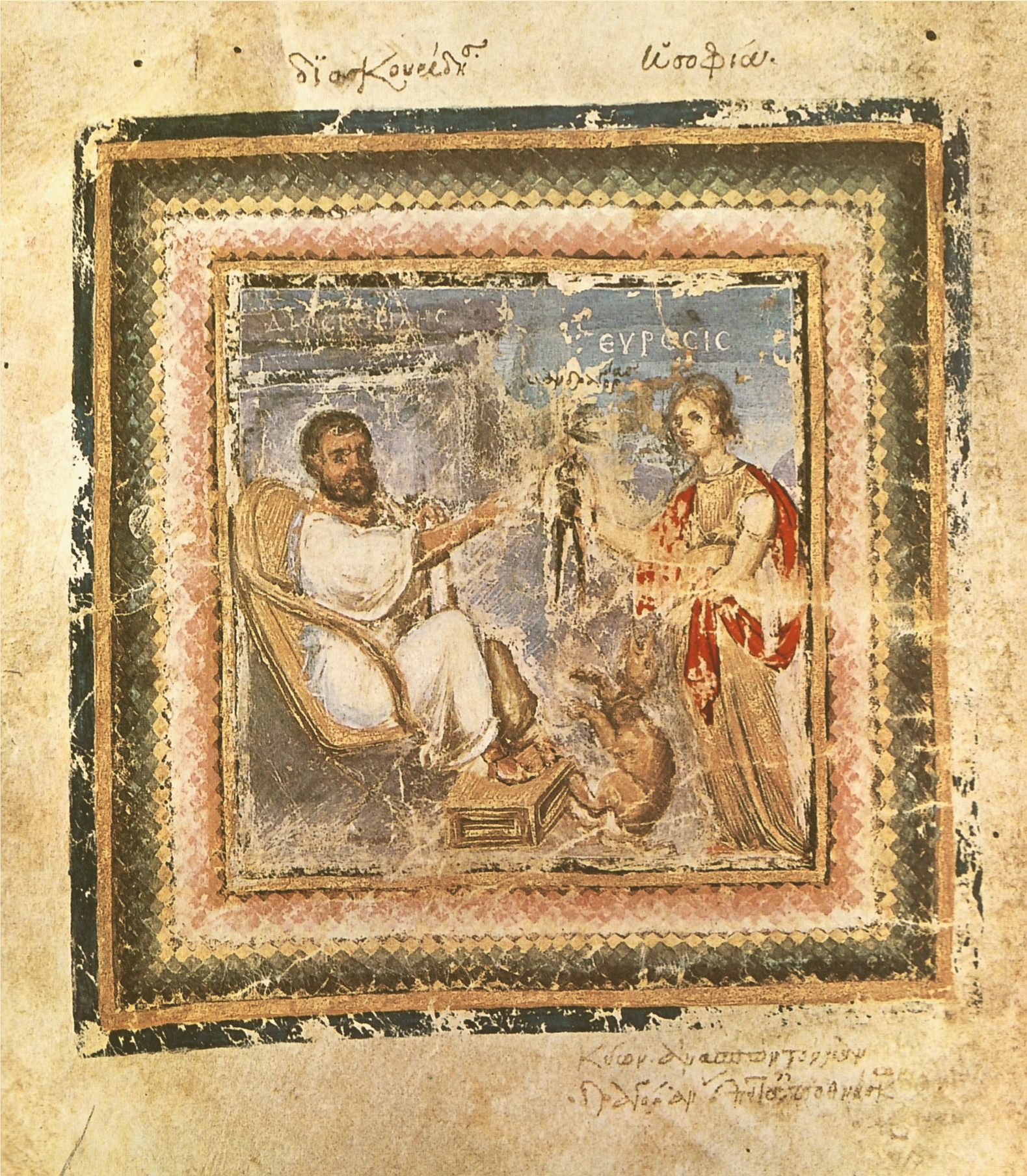

Doctors have made use of me since the time of the Ancient Greeks.

Around 50 AD, the physician Pedanius Dioscorides described my medicinal uses in his ‘Materia Medica’, a five-volume encyclopaedia that included over 600 plants.

He said I was good for the treatment of burns, dislocations and abscesses.

Other members of my family are just as capable.

For instance, the giant snowdrop (Galanthus woronowii) contains a compound used to improve memory in people with Alzheimer’s disease. These patients’ brains lack ‘acetylcholine’, a chemical that works to transport nerve impulses.

The degradation of this chemical can be slowed down by galantamine, which is extracted from Galanthus bulbs.

It can’t prevent Alzheimer’s disease, or slow its progress, but in some patients it can help to reduce the symptoms, like memory loss and confusion. Nice, right?

Today there are bulb growers that cultivate the giant snowdrop on a large scale for pharmaceutical companies.

Still, you’re better off not eating anyone in my family.

We also contain a poison, lycorine, which can bring on vomiting, stomach-ache and diarrhoea. It happens quite a lot, actually, when people think my bulb is an onion…

Type ‘Easter’ into any search engine and chances are you’ll see a picture of me. That’s because I’m an ‘Easter flower’.

Not an official title, of course, but a popular name for any flower that blooms around the time of this Christian holiday, and will therefore turn up on just about any website giving ‘Easter table tips’.

However, the daffodil season actually starts much earlier than this. In February you can already see quite a few of my yellow brothers and sisters poking their heads up.

And by the way, we’re not all yellow! There are white, orange, and even pink daffodils.

There are small daffodils and big ones, daffodils with leaves and without, daffodils with a strong fragrance and those with none at all, daffodils with star-shaped flowers and a white ‘crown’ (as my inner petals are called), or oval flowers and a golden crown.

People disagree about exactly how many varieties there are, but there are 65 for sure, and some think there are 85.

The best-known is the bright yellow ‘trumpet daffodil’, so called because of its trumpet-shaped corona.

As if it’s playing us a tune – ‘don’t worry, spring is on its way!’ – just as an Easter flower should.

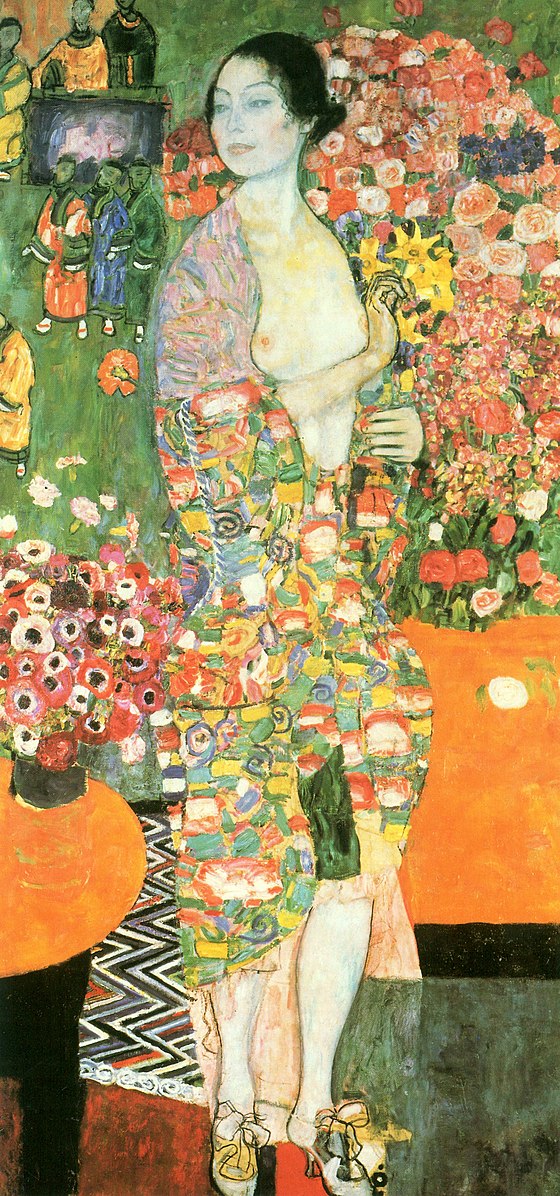

In most of the paintings in which I appear I have a rather minor role. For example, in Gustav Klimt’s mosaic ‘Die Tänzerin’ (1916-18), in which a dancer holds a small bunch of daffodils.

Or ‘When flowers return’ (1911) by the 19th-century Frisian artist Laurens Alma-Tadema, in which three young women in white robes dance together, linked by a long chain of interwoven daffodils.

But in some paintings, I am the star of the show.

Like the one painted by the French impressionist Berthe Morisot in 1885, of a teacup full of tiny daffodils.

My personal favourite is ‘Jonquils I’ (1936), by Georgia O’Keeffe.

In 1933 this American artist was well on the way to becoming a star when she suffered a nervous breakdown and was admitted to a psychiatric hospital. She had been worrying about a large commission, and to make matters worse her husband, the successful photographer Alfred Stieglitz, had taken up with another woman.

When O’Keeffe was allowed to go home, she hired her own studio and slowly started painting again.

Bit by bit she recovered, and three years after having been admitted she took a canvas, her boldest paint and a large brush, and she painted two stunningly lifelike, gigantic yellow daffodils against a pink background.

Why? I think that with a flower that symbolises a new beginning O’Keeffe was letting the whole world know: ‘I’m free, and I’m back!’

Hi, my name is Daffodil. Do you want to know where name comes from?

ELSPETH DIEDERIX

NARCISSUS

(NARCIS)

2022, 45 X 30 CM

Daffodil

name

Narcissus

Height

45-50 cm

Flowering time

April-May

Family

Amaryllidaceae

name

Narcissus

Height

45-50 cm

Flowering time

April-May

Family

Amaryllidaceae