Colochicum Autumnale

Autumn crocus

Naked Lady, The Dutch folk name of this plant, ‘tijloos’, is unusual. According to the Dutch Etymological Dictionary it has to do with the fact that I flower outside the usual season:

I bloom in late autumn, and my fruits arrive in spring. So I’m a ‘timeless’, ‘tijdloos’, plant whose name has corrupted to ‘tijloos’.

In other places in the Netherlands I’m known as ‘herfstbloem’, ‘herfstblôme’ or ‘haarfstblôme’ (autumn flower) for the same reason.

In Groningen they call me ‘bloem-zonder-blad’ (flower-without-leaves); my flowers bloom on a bare stalk long before I show any leaves.

In other parts of the country they have come up with lots of similar funny names: ‘kale juffer’ (naked damsel), ‘kale madame’ (naked lady), and ‘nakende wiefkes’ (bare wifey). In Utrecht they say ‘naakt mannetje’ (naked little man). Well, thanks very much!

My Latin name Colchicum autumnale comes from Colchis, an area on the eastern edge of the Black Sea – now in Georgia – which is said to have been my original home; and ‘autumna’, Latin for autumn, for my flowering period, from September to November.

Another view is that my name is linked to Medea, the notorious sorceress who – according to a rather grim Greek story – lived in Colchis.

Medea knew all there was to know about poisonous herbs, and added me – a deadly plant! – to a magic potion that rejuvenated her lover, Jason, and helped him retrieve the Golden Fleece.

That was nice of her, but she used the same magic potion to avenge herself on Pelias, Jason’s uncle, after he refused to give Jason dominion over Iolcus.

Medea told Pelias that the drink would make him, too, younger, though he would have to let himself be cut into pieces first. Spoiler alert: it didn’t work, and Pelias died.

Whether I really did originally grow at Colchis is open to question.

The Ancient Greeks, who called me ‘kolchikon’, may have confused me with ‘Colchicum variegatum’, a lilac-coloured crocus which certainly did grow there, but was much less poisonous.

In the Middle Ages I was seen as a magical herb. If you carried my bulb you were protected against toothache, and also against the dreaded plague.

In folk medicine I was also used to treat jaundice. No wonder they called me ‘levensbloem’ (flower of life). Ironically, I’m actually very toxic; a few grams of my seeds could easily kill a child.

People used to use my seed pods as a baby’s rattle, because the little seeds inside made a funny noise when the pod was shaken. Very dangerous, of course!

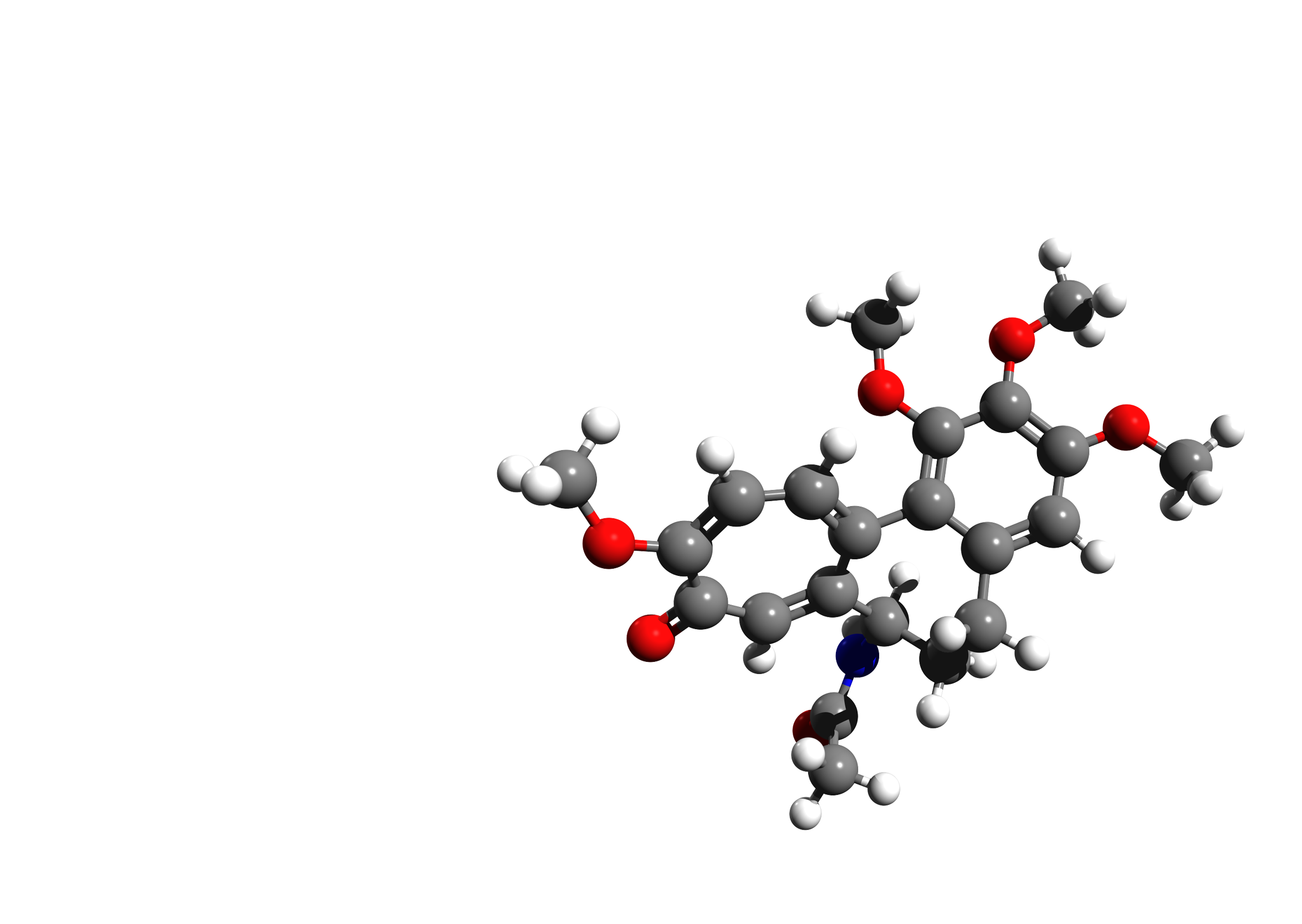

The toxin in my seeds, and also in my bulb and flowers, is called colchicine. It’s an alkaloid that interferes with cell division. If you eat too much, then to start with you can count on symptoms like diarrhea, stomach-ache and vomiting – worrying, but not immediately life-threatening.

The real trouble only starts after one to seven days: heart failure, kidney failure, liver failure and fits. Eventually your lungs stop working. And there’s no antidote.

Even so, small doses of colchicine can also be beneficial. It’s sometimes prescribed for gout (the painful inflammation of a joint) and sometimes for inflammation of the pericardium.

Patients who have already had one heart attack run less risk of a second if they take a pill containing half a milligram of colchicine every day.

But they have to be careful: there’s only a small difference between a therapeutic dose and a deadly one!

The poet T. van Deel was fascinated by me. He drew me hundreds of times in his final years, and also gave my name to his last collection of poems. It included the poem ‘Herfsttijloos II’. It goes like this:

Born from its flaking bulb the stem rises steady and straight, white at first and later at the flower tending to the purple of All Souls’ Day.

Their bulbs become exhausted and seem even older than they were but the bloom is boundless as if a nest full of birds were holding their beaks lifewide open loud and irrepressible

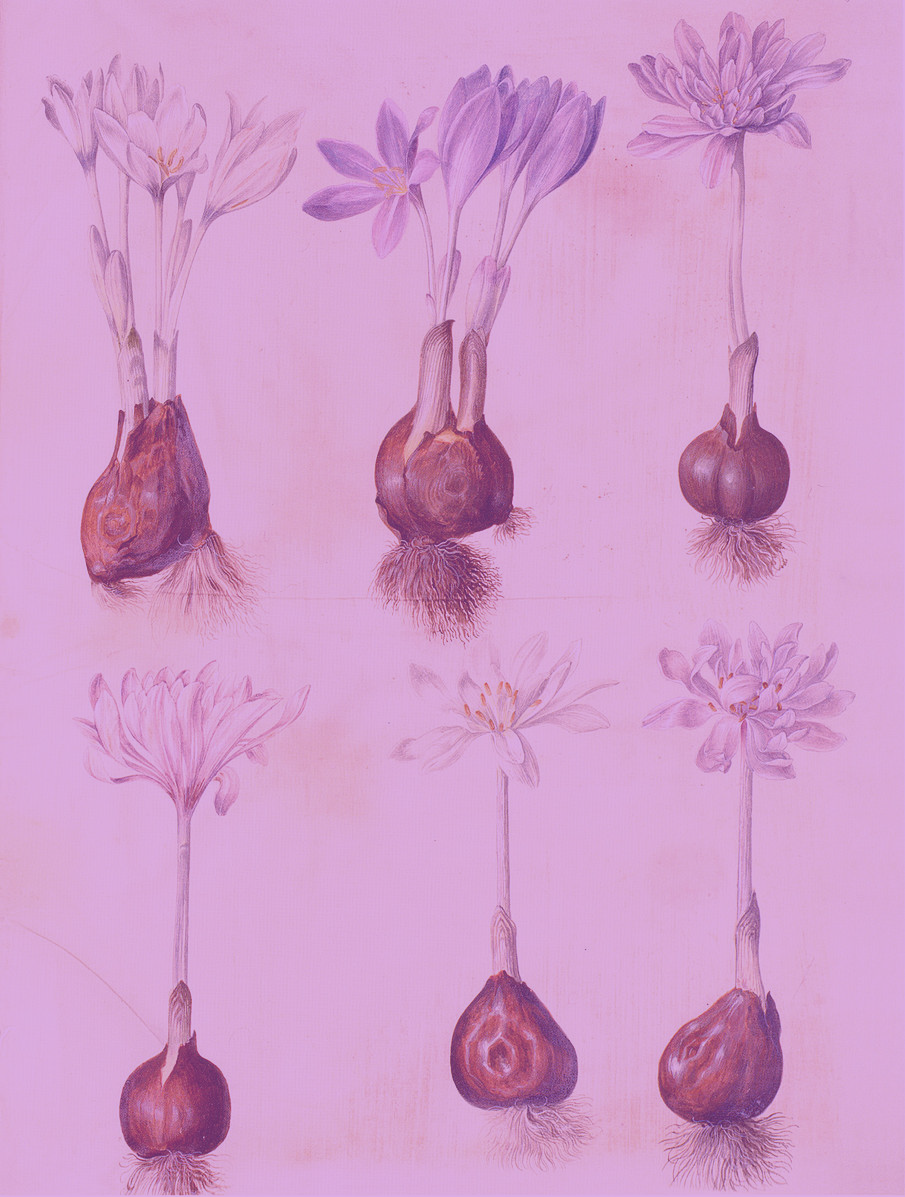

During the Enlightenment, the painter and botanist Pierre-Joseph Redouté was the favourite artist of the Parisian ‘beau monde’. Queen Marie-Antoinette, the wife of King Louis XVI of France, engaged him to paint her plants and named him ‘painter of the nation’.

When Napoleon seized power, his wife Joséphine Bonaparte turned out to have the same love of flower paintings. In 1802, she had Redouté draw all the flowers in the garden of her château Malmaison in Paris.

The result was dozens of illustrations that decorated the walls of Joséphine’s red bedroom as well as the pages of the art book ‘Les Liliacées’.

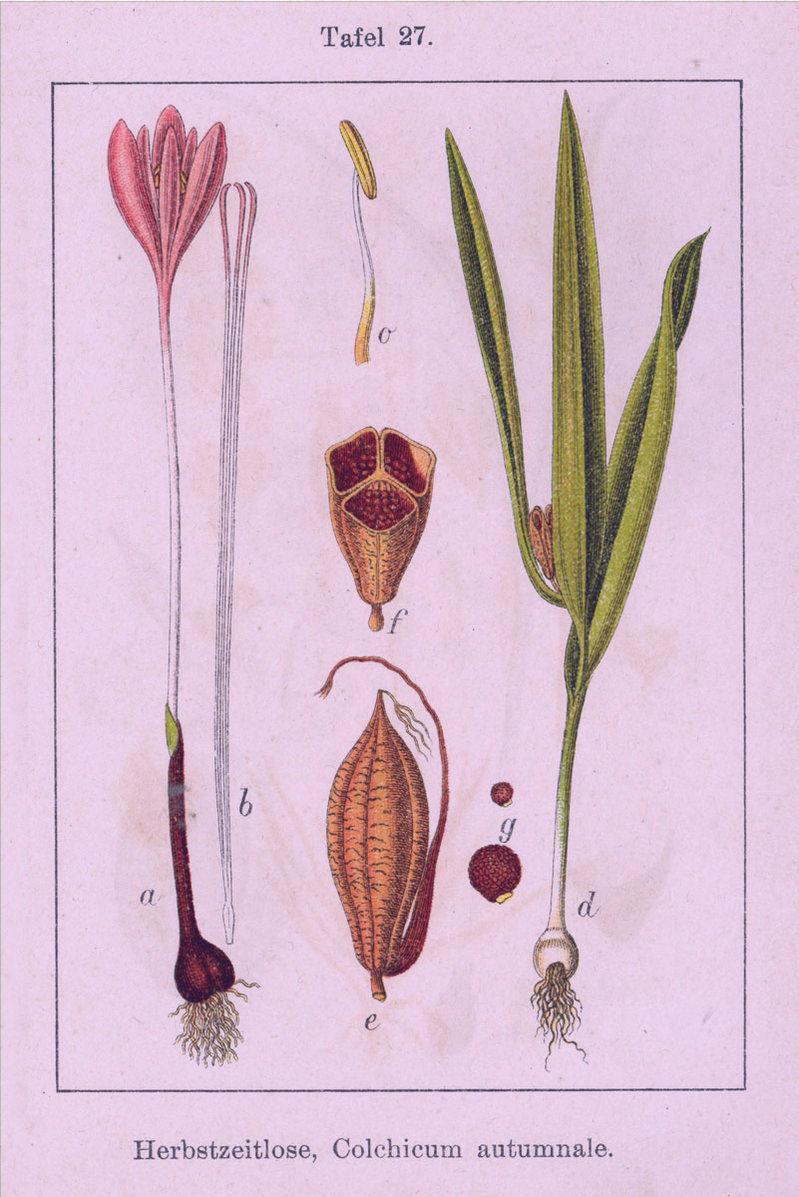

One of these illustrations is of me. Redouté has drawn me in extraordinary detail. As a botanist he knew all about my growth and structure.

First he sketched my brown, walnut-like bulb, then my white stem, and finally my delicate lilac flower petals, both open and closed.

Alongside me he also drew my dark green upright leaves, forming a kind of bundle, which are absent when I bloom. So he drew me in all my guises – nice for the viewer, and important for botanical science.

Originally I’m from the Mediterranean and western Asia, but today you will find me in large parts of Europe, especially in woods, alongside dune paths and in damp meadows.

You don’t see much of me in the Netherlands. I can be found here and there in parts of Zuid-Limburg and on the border with Belgium, but I’m on the so-called Red List for plants,

which means that I’m a very rare species faced with extinction. My status is ‘under threat’. So if you see me, please leave me in peace.

If you live in the north of the Netherlands and you’d like to see a lovely autumn crocus, garden centres usually have ‘herfsttijloosbollen’ bulbs. Most of them look a little different to me, though, so for the real thing you’ll have to go south of the rivers.

Hi, my name is Autumn crocus. Do you want to know where my name comes from?

ELSPETH DIEDERIX

COLCHICUM AUTUMNALE (HERFSTTIJLOOS)

Autumn crocus

name

Colchicum autumnale

Height

15 cm

Flowering time

September-October

Family

Colchicaceae

name

Colchicum autumnale

Height

15 cm

Flowering time

September-October

Family

Colchicaceae